The recent collapse of Carillion plc raises serious questions about the viability of corporate business models. This might not be an isolated event — presenting a major wake-up call for businesses, everywhere. The question is, what should be done: Can we avoid the fall of giants, or are we witnessing an inevitable process of creative destruction?

The bigger they come, the harder they fall — so the proverb goes. And, until recently, they didn’t come much bigger than Carillion: the UK’s second biggest construction and services company — having generated a massive £5.2 billion of sales revenue in 2016 — collapsed, dramatically, on 15th January 2018. The business had accumulated debts of £900m, and with only £29m cash in the bank, compulsory liquidation was the only option. A true giant of British industry had fallen.

The demise of Carillion is seriously bad news. Bad news for 43,000 employees, worldwide — 20,000 of whom are in the UK — now facing an uncertain future. Bad news for Carillion’s former customers; either having to re-assign essential services, worth billions of pounds — or recover partially completed projects, estimated to be around 450 in number across the UK. The scale and cost of disruption is enormous.

The shockwaves radiate far from the epicentre. There is further bad news for former suppliers — with up to 30,000 small firms in the supply chain owed money — likely to receive less than 1p for every pound they are owed. Many of these small businesses may now face insolvency, themselves. Then, there is the serious potential for thousands of direct and indirect job losses, along with the accompanying feedback effects arising from the loss of earnings and self-esteem, spreading further economic and social impacts across many communities.

The only winners are the hedge funds and financial speculators that made tens of millions of pounds by quietly betting that Carillion would run into financial distress. This dubious practice had the effect of driving Carillion’s share price further towards oblivion — until it became worthless. Long-term investors, including pensions funds, stand to lose a great deal, too.

From crisis to challenge.

A major corporate collapse of this nature also presents a major challenge for all of us in the sustainability movement, especially within the corporate sector. Carillion was considered a champion — striving towards ‘making tomorrow a better place’ — highly ranked by various indices, including the BITC Corporate Responsibility Index; rated with 4 stars (96%) in 2016. Presumably, business model sustainability wasn’t scrutinised too closely at that time.

This challenge raises some serious questions. While we’re all busy, reducing environmental footprints and improving community impacts, are we somehow missing the greater, over-riding sustainability challenge? To be blunt, if we are not making inroads into the commercial sustainability of corporate business models, then all our good intentions will be in vain. A much more rigorous approach will be necessary, if we are to help avoid such collapses in the future.

So, what went wrong? The short explanation appears to be the usual story of corporate greed, short-termism, and excessive risk-taking. Hubris.

To be fair, Carillion is not the first — nor probably the last business — to be found wanting on these issues.

Hollow business model.

At the heart of Carillion’s downfall, lay a hollowed-out and vulnerable business model. The company had been fairly successful in the past — but, at some point, something changed. The model was no longer about creating value, but increasingly shifting towards extracting value, apparently for the short-term benefit of shareholders and company directors.

“At the heart of Carillion’s downfall, lay a hollowed-out and vulnerable business model.”

As with most corporations, Carillion faced continuous pressure to deliver year-on-year growth — even in the face of a challenging market — in order to meet market expectations; to ensure a good return for its shareholders, as well as covering business costs and servicing its debts. The cold edge of commercial reality bites hard — but, so does an unsustainable economic model.

Increasingly, Carillion had taken on risky projects — some of which were failing, adding to the company’s mounting debt burden. Four specific contracts have since been highlighted; three in the UK, and one in the Middle East, which were beset with delays and mounting costs. To offset this position, the company started withdrawing from markets in Canada and the Middle East, while incurring further short-term costs.

In an industry known for slender margins — typically down to 1% for UK construction in 2016 — this left very little room for error. The additional costs and losses were piling up — adding to an already significant debt burden. By Sept 2017 net debt had almost doubled to £571m on the previous year. The company was also struggling with a pension deficit of £711m. The total market value of the business was worth only £200 million.

Clearly, the numbers were no longer working, and it was no surprise that the company could no longer call on its investors to shore up its finances. Drastic action was needed to support recovery, with the directors considering a rights issue, along with further asset sales to tackle the growing debt.

Of course, the ongoing debt challenge is only manageable if there’s enough profitable business coming through the pipeline. There were problems here, too — not least due to Brexit-related uncertainty.

Meanwhile, the band played on. In the face of such severe challenges, the Carillion board continued to pay out large dividends and executive rewards, bringing accusations of creating a giant Ponzi scheme. Effectively, the company was using debt to continue underwriting the cost of business operations, and to subsidise dividends and executive rewards.

“Like the gambling addict, perhaps the board felt they could play their way out of trouble?”

Like the gambling addict, perhaps the board felt they could play their way out of trouble? All they needed was a bit more cash, just to keep the game going, and soon their luck would surely change?

In the end, they could no longer continue to defy gravity. Boom! Carillion’s share price lost 94% of its value within the space of only one year. The business could not be sold as a going concern — there was nothing of value left to sell: liquidation was the only available route.

Then, what should be done?

As the dust settles, there will no doubt be calls for more tick-box regulations to improve corporate governance, so we might avoid similar catastrophic collapses in the future. This move could be necessary, but might not be sufficient. As with other corporate collapses, we also face broader questions on boardroom culture, along with the role of company directors, their focus and capabilities. We might need a more fundamental rethink.

According to a McKinsey survey, only 34% of company directors believe their boards fully comprehend their business strategies. Even fewer appear to understand the business model, with only 22% aware of how their firms create value. And, only 16% understand the dynamics of their specific industry.

These results are truly staggering, and perhaps help us to understand how easily a Carillion-style collapse can happen. They might also explain how ‘trust’ in our businesses and institutions is at an all-time low.

Then, as we reflect further, beyond the simple mechanics of ‘understanding’ their businesses, we can only wonder at how many company directors truly scan the landscape for material risks and opportunities, in order to sustain a long-term, profitable enterprise? Do we really face such a massive board-level capability gap?

Carillion’s directors have, themselves, subsequently admitted they failed to question their own business model. This is important territory — where all boards need to go, going forward — ably supported by their Chief Sustainability Officers (CSOs). Although, this should not be some cursory exercise in greenwashing.

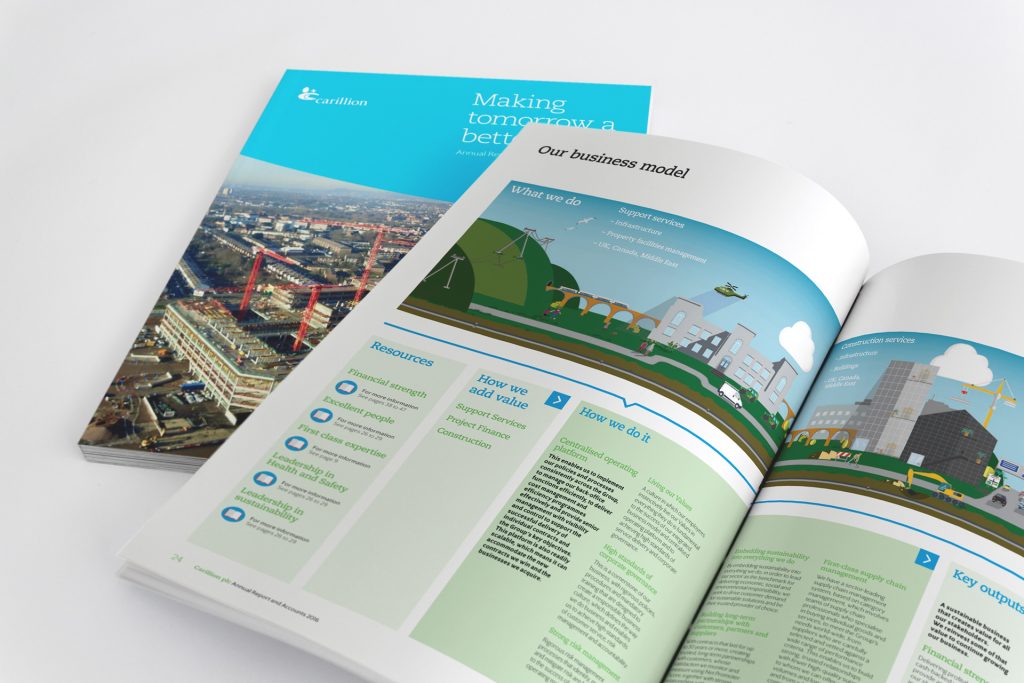

If we take a look at Carillion’s most recent articulation of its own business model, shared within its 2016 annual report, we get little real sense for how Carillion actually made its money — where risks lie, and where there might be further opportunities for authentic and profitable income — let alone gain any appreciation for whether the company had a responsible business model, or not.

And, presumably, Carillion’s management, staff, and even investors might not have been able to readily discern these insights, either? Opaque, is the word.

As with many glossy corporate reports, these days, there can be a tendency to share superficially-attractive graphics, but offer very little in the way of real business acumen. A triumph of style over substance. Carillion is not the only one, rather lacking in this respect — this is a common challenge.

We need to see more authentic, sustainable business models that demonstrate the mechanics of how they deliver fair and robust returns — in the short-term and into the future — while providing for suitable levels of reinvestment, yielding a fair return to investors, but still accounting for the true cost of a company’s activities, and how they operate within environmental and societal limits: invoking respect for all stakeholders, including employees and their valuable jobs. This level of sophistication is very rare in current corporate practice.

The wake-up call.

The Carillion model — with all its inherent risks to sustainable growth and profitability, and a growing debt profile — was, ultimately, too fragile. Yet, this situation could happen to almost anyone; the business model challenge is not simply constrained to UK construction and government contractors.

Business models in many sectors are being stretched, tested towards breaking point: no longer able to deliver the illusion of continuous growth in sales and profits; no longer able to defy gravitational forces of debt, market saturation, and growing risks. Other high-profile companies could soon follow, perhaps sooner than we think? Could Retail become the next stranded asset in the UK? There is plenty of evidence of poor performance, and little in the way of positive news ahead. And, once again, the hedge fund vultures are circling overheard — now betting against British retailers.

“Conversely, anyone can answer the wake-up call.”

Conversely, anyone can answer the wake-up call — and start the journey towards turning a risky business model around. DONG Energy saw the writing on the wall for fossil fuels, over a decade ago — and, since then, has been successfully transitioning its model towards renewable energies. The energy company has now achieved 67% reduction in carbon emissions, 82% reduction in coal, and now uses 64% renewable energy in its generation of power and heat. Through the process of de-risking the business model, its market value — subject to the usual market fluctuations — has continued to rise. DONG Energy has also recently re-branded as Ørsted to commemorate its successful divestment from oil and gas.

Even cigarette manufacturer, Philp Morris, is looking to develop a new business model, driven by a bold ambition to “stop selling cigarettes in the UK.” A seemingly counter-intuitive move, the board now shares an important admission, “We have a duty to our business that we ensure we have a viable business going forward, so we’re investing in alternatives.”

Let’s get this straight; if these two companies can reinvent their previously dysfunctional business models, anyone can. Boards and their CSOs need to take heart from the great examples out there, and get to grips with the full business model sustainability challenge, and fast.

Can we avoid the fall of giants?

That things are unravelling is not surprising. There have been calls for deeper work in developing truly sustainable business models for many years. The only real surprise is that problems have taken so long to surface.

Can we now avoid the fall of giants? For Carillion, it’s now too late. For others, there is still time — just.

—

Mike Townsend is founder and chief executive of Earthshine Group, and author of The Quiet Revolution (Routledge, forthcoming).

This is an abridged version of an article, originally published on Medium.com

Follow Mike Townsend on Twitter.